The fight for trees and their benefits

By John Fitzsimmons

Most people reading this journal probably admire and appreciate trees. Some might not be huge fans, but I’d like to think there are very few tree-hating readers. But the haters, more who just don’t care and others who simply have other (usually political or monetary) priorities, are preventing or limiting the benefits of trees accruing to society and the world at large.

The general debate about how we live with trees ebbs and flows. Recently, various news sources have, coincidentally, published negative reports across our country. Close to home, this year alone and ignoring the large-scale weather extremes, some local news reports referenced:

- A Canberra man being “baffled” by the ACT’s refusal to remove a “large dangerous gum tree” from his property after a branch from the tree fell and caused his house’s roof to collapse “narrowly missing a sleeping 2-year-old child”. The ACT government had reportedly deemed the tree to be healthy and stable.

- Residents of a Victorian retirement village say ‘cutting and trimming’ of neighbouring “gum trees” wouldn’t be enough. Reported comments include “the trees are beautiful in the bush but not in the suburbs” and “we want them chopped”.

- Complaints are often made about tree roots impacting footpaths (often affecting older citizens’ mobility on foot or on ‘gophers’), fallen leaves, fruits and small branches blocking gutters and drains and soiling washing on clotheslines, concerns about shading as previously acceptable or tolerated trees mature, and a more contemporary one – the effects of fallen leaves and sap, and shading, on rooftop solar panels.

- A young girl was hit by a falling tree branch during a visit to Government House in Canberra. The tree had reportedly been assessed as safe in the previous 6 months.

- Another Canberra resident reported a falling tree branch impacting her house after reporting concerns about the tree in question over four years without meaningful response from (local) government.

- An historic 145-year-old 10m ‘Jerilderie Red’ tree at Camperdown in Sydney was chopped down because its roots had supposedly impacted a concrete driveway. The tree had unique provenance – apparently being a cross between an Illawarra flame tree and a Kurrajong (both Brachychitons) and the original ancestor of all such trees. The ‘root problem’ was apparently reported by the property’s tenant and destruction authorised by the landlord-NSW state government department responsible, without reference to the tree’s botanical and historical significance or health.

- The City of Glen Eira in Victoria last year suffered its first-ever act of widespread tree vandalism leaving an estimated $200,000 in damages. In one weekend about 200 newly planted trees across 8 sites were “cut at the base with a hand saw, snapped at the base and, in some case, completely ripped out from the ground”.

- About 300 trees were killed at a reserve in Longueville, Sydney. The Lane Cove Council mayor described it as the worst act of environmental vandalism in the area’s history.

- In Perth’s Ocean Reef, all but one of 20 newly planted Callistemon and Melaleuca trees were chopped down by vandals. It was but one in a series of attacks there, with 56 trees poisoned or cut down in the previous two years.

- The ACT government decided to remove 140 trees as part of the Australian War Memorial expansion.

- Meanwhile, local residents are fighting against the destruction of a near-50 year old eucalypt on the grounds of Alfred Health’s Sandringham hospital in Melbourne’s bayside suburb. Alfred Health says two independent arborists found the tree needed to be replaced due to branch failure, internal decay, and structural defects. But Bayside City Council’s arborists reportedly disagree with that assessment, with locals believing proper pruning could stop the tree from hurting anyone.

Of many of the drivers for anti-tree sentiments – ‘safety’ is high on the list. Monetary or ‘personal benefit’, including ‘improving’ views or removing ‘obstacles’ to building and development, are close behind. Often those sentiments are focused on individual or small groups of trees but there is an undercurrent of broader dislike, even hatred, of trees generally in certain sectors of society. These drivers have been discussed before.

Attacking trees ‘compromising’ waterfront views are especially common and usually closely connected to perceived property values. But now, according to some observers, more curious instances of tree vandalism are cropping up, including tree destruction, such as the case in Glen Eira, Melbourne, where there was no view being obstructed; if anything, the trees were the view, and it was suggested the attack was motivated by feelings about the Council.

The value and benefits of trees are perennial topics, with more objective and quantified values emerging regularly.

Broadly, we know how urban trees and plants do more than just beautify city landscapes; they purify the air, reduce urban heat islands, provide recreational spaces, and even boost property values. Overall, they silently contribute to our well-being. Recent University of New South Wales and University of Wollongong research analysed the living arrangements of 100,000 urban-dwelling Australians and their local neighbourhoods, along with 10 years’ worth of hospital and health data. The study found that a 10% increase in tree canopy reduces heart disease indicators for people living in houses, including a 4% reduced risk of cardiovascular disease-related mortality and a 7% decreased risk of heart attacks!

Yet the same cardiovascular benefits aren’t necessarily as evident for unit dwellers. One reason is that apartments are normally quite dense and maybe even crowded, the researchers suggested. If you plant the same number of trees in a low-density area and then a high-density area, the ratio of trees to people changes.

The study findings were published in the journal Heart, Lung and Circulation and the authors (Professor Xiaoqi Feng and Prof Thomas Astell-Burt) are the founding co-directors of the Population Wellbeing and Environment Research Laboratory.

But what is being done for those of us who do see the value and benefits of trees? What more can we do?

One of the biggest issues is inconsistency in laws and regulations across hundreds of Australian state and local government jurisdictions. Allied to that is the strength of the laws and the scale of penalties – potential and actual.

A petition was recently introduced in the ACT Legislative Assembly to “fix” the ACT’s tree removal guidelines, which are intended to “dovetail with the current government review of the Urban Forest Act”. The initiator/s hoped “the legislation could … make some adjustments, most notably lowering the threshold at which action can be taken on a dangerous tree … but also to genuinely take into account the risk to property and life and not just assess the health of the tree”. Solar access, fence damage, excessive winter shade are now ‘relevant considerations’. The ACT’s Urban Forest Act had been in place since 2024, giving automatic protection to all trees on public land and trees above a certain height on private land. But, ACT City Services Minister Tara Cheyne was reported as saying some of the criteria were found to be “very limiting”, so some of those regulations were changed in late 2024. Now the act is under review again, focusing on the scope of reasons a potentially dangerous tree can be pruned or removed. Ms Cheyne said “we have now, through the update to the decision criteria, given the conservator and his office more latitude to consider if the tree is dead and it’s not offering any ecological benefit, can it be removed. If a tree is negatively impacting things like a person’s solar access, their washing or their fence, “those are relevant considerations” under the updated Act.” It will give decision makers a lot more flexibility than they had, she was reported as saying.

In many jurisdictions, damage to Urban Green Infrastructure (UGI) is considered a minor offence with commensurate minor penalties. This process is also notoriously hard to identify suitable charges, gather sufficient appropriate evidence, and secure adequate convictions. Witnesses or suitable CCTV evidence is not always available and the increasing use of portable and more unobtrusive tools such as battery-powered saws doesn’t help.

- Councils can apparently issue on-the-spot fines for illegal tree removal, and those responsible for acts of criminal damage can face fines up to $218,000 and a maximum penalty of 10 years in prison in Victoria, but that’s a rare outcome.

Nor do the laws against UGI damage always align with a government’s publicly stated community objectives. Consider:

- In a recent Victorian case, a developer was successfully given permission to build on land after illegally clearing vegetation. The developer had cleared about 1.4ha of vegetation illegally and was criminally convicted and fined $225,000 in the Victorian County Court. However, the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT) later approved the company to build a multi-million-dollar development on the site due to this absence of vegetation(!?). In making its decision, VCAT cited its high industrial value and approved the $6.8 million project with conditions for the developer to relocate endangered species and fund environmental offsets. Go figure.

At a Treenet symposium last year civil engineer Ray Verrati, who had worked on some of Melbourne’s largest master-planned communities, looked ‘retrospectively’ at what had gone on and observed “we can do this better”.

“Our profession sometimes sees urban greening as just the add-on; the easy bit at the end of the project. Usually, in development, money has already come in and the focus is to move on. I would like to change that narrative and say it’s quite a complex topic and we need to properly consider it.”

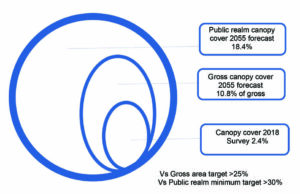

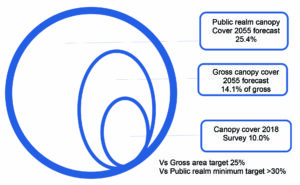

He offered as examples Wyndham and Whittlesea (on Melbourne’s west and north fringes respectively), two of the city’s biggest growth areas. He referred to research by Melbourne University’s Patricia Torquato who measured actual tree growth rates in those areas over 15 years and forecasting future canopy cover (Diagrams 1 and 2).

“There’s an obvious mismatch between policy, design and what’s being done. Tree Canopy Targets are not being met due to poor planning, design, construction and maintenance practices.” He reminded the audience that engineers solve technical problems that make things better for the world. We need to acknowledge there’s a problem and:

- upskill our urban green knowledge with collaboration with specialists

- do the easy stuff well – increase tree quantities, improve tree growth zones, and improve the permeability of road reserves

- undertake R&D for the harder stuff

– review and improve the regulatory framework

– improve pavement/tree growth zone onterfaces

– produce a specification for backfill of tree growth zones “do the job it has to do – for a tree”

– review the vertical and horizontal alignments of service asset. One simple revision of the usual 16m road reserve increase permeability by 50% increased . the soil volume by 70%. Tree numbers and canopy cover were also improved (Table 1)

– improve urban design and housing mix

- agree on technical standards

Verrati suggested the development industry had a cultural problem and could improve its attitude to this important subject. For engineers, it’s about being really clear on what the targets are, codefying it and measuring it, he said.

“We build these lots and the capital cost of the landscape is probably less than 3%. If you made that 4% I think you would make a big difference.

“A lot of what I see does not include the many experts that are needed on a site-specific basis; every site is different. We need to inform the design and the execution to get the best outcome.

“As a very broad comment after 30 years in land development I think the capacity and knowledge generally around urban greening is “up and down”, he observed. “I often wonder if there should be an Urban Greening discipline established that draws a thread through all these experts and how that could happen. There are lots of great ideas but what is missing is that thread that draws it all together.”

Different vegetation standards and interpretations also contribute to the problem. In the Sandringham situation (above) arborists used by Alfred Health say the tree is unsafe while the local council’s arborist disagrees – different professional interpretations. Arborists, instead of lawyers, at 10 paces?

Coincidentally Arboriculture Australia recently celebrated a ‘win’. Arboriculture retained a spot on the Australian Core Skills Occupation List after a government review. ‘Arborist’ had been at risk of being removed from the list – the main document used by the Australian Government to guide immigration policy and allocate visa categories for skilled workers.

Following major bushfires. partly associated with above ground electric wires, there was a move to maintain (more) generous clearances between power transmission lines and surrounding trees. This was carried over from forested rural areas to street trees in urban areas; many examples and accusations of ‘tree butchering’ and unnecessary tree removal followed. Currently, Treenet is supporting the Make Victoria Greener campaign. The campaign has a single objective: to protect Victoria’s urban tree canopy from unnecessary destruction caused by excessive powerline clearance pruning.

However, last year an expert committee, the Electric Line Clearance Consultative Committee (ELCCC) that reports to EnergySafe Victoria, formed an advisory group including representatives of all electricity providers, local government, rural communities and others. The group unanimously recommended to the ELCCC that the clearance space around low voltage (LV) conductors in low bushfire risk areas (LBRA) be reduced from 1000mm to 300mm. But the ELCCC opposed the recommendation and opted for a 500mm clearance requirement instead, without any data or due process to support this. ELCCC also opposed some proposed changes to practices for high voltage conductors, changes that would have significance in rural Victoria.

The farce of such “consultation” then saw legislation introduced to the Victorian Parliament to eliminate the ELCCC and to extend the regulation period from 5 to 10 years. EnergySafe Victoria may take no responsibility for urban vegetation during climate change, and significant losses of urban trees and declining canopy cover, but government retains responsibility.

Opponents of the decision, including The University of Melbourne’s Greg Moore OAM, also a member of the ELCCC, said reducing the amount of foliage it cuts back would enhance the state’s tree canopy, and deliver $1 billion of benefits, without any extra taxpayer investment. They also maintain the line clearing regulations in Victoria, and particularly those for LV conductors in LBRA, are not fit for purpose as the climate changes and warms.

Energy Safe Victoria is right to be concerned about possible electrocution and fire risk associated with conductors, they say, but there is no evidence of these being associated with LV conductors in LBRA.

Meanwhile a national push to prioritise Urban Green Infrastructure (UGI) is gaining momentum, with 12 peak industry bodies* rallying behind the cause. Together, they represent more than 23,900 professional members and over 500,000 Australian jobs across urban planning, design, engineering, horticulture, arboriculture, parks and leisure, and green infrastructure supply sectors. At the heart of this effort is the National Urban Green Infrastructure Round Table – a new collaborative initiative dedicated to showcasing the critical role of UGI in building resilient cities that enhance biodiversity, improve public health, and drive economic prosperity.

Australia’s amenity horticulture sector already produces nearly $3 billion worth of trees, plants, and turf. But data highlights an urgent need to increase investment in UGI and embed it into mainstream urban infrastructure spending.

“UGI as a national priority is more than just an environmental benefit; it is a critical piece of our cities’ infrastructure that delivers measurable climate resilience, biodiversity, and community wellbeing,” David Jenkins, CEO of the Institute of Public Works Engineering Australasia, has said.

“Yet, UGI is still often treated as an afterthought. Our cities and regions need to move from ‘nice to have’ to ‘must have’ when it comes to green infrastructure.”

Despite its benefits, UGI is frequently sidelined in planning and investment decisions, lacking clear accountability for its establishment, management, and long-term health and sustainability. The member organisations of the ‘round table’ member organisations have released Australia’s first industry-supported Position Statement on Urban Green Infrastructure. It outlines six key recommendations to advance UGI across Australia. These include calls for:

● formal asset classification

● national standards

● long-term funding

● workforce capacity building, and

● embedding UGI as a key component of urban infrastructure planning

In individual cases, local councils have responded to attacks in various practical ways outside the legal and regulatory system. These have included:

- blocking views resulting from UGI vandalism with shipping containers (Brighton-le-Sands, NSW)

- creative pruning of dead mature trees to create potential homes for a range of animals including possums, grey shrike-thrush birds, parrots and micro bats (City of Mitcham, SA)

- installing signage on and near damaged trees with monetary values applied to the tree, as well as carbon offset figures e.g. My name is Jacaranda, I am 15 years old, I am valued at $29,791, my replacement cost is $3165, my annual cost of care is $510, I would sequester 100 tonnes of carbon in my lifetime. (City of Perth WA)

- the City of Perth has increased penalties for illegal tree destruction from $500 to $5,000

- a 7m long, 2m high, bright orange banner was erected in response to the destruction of trees at Longueville (Sydney). The banner was created to obstruct any potential harbour views the culprits may have benefited from, with a sign reading: “Trees shouldn’t die for a view.” That banner will stay in place until the new trees reach their original height. (Lane Cove City Council NSW)

So, as professionals like Ray Verrati observe, Greg Moore agitates, and the National Urban Green Infrastructure Round Table gathers, there is much common ground, many viewpoints, and random obstruction. Obviously, as the saying goes, “there is a lot more to be done”.

Thanks John, that was a great read and 100% true