Finding sympathy with a changing natural landscape

By John Fitzsimmons

As it exited pandemic times the biennial Australian Landscape Conference 2023 attracted impressive audience numbers and was another signature offering of diverse and accomplished presenters. While the 2023 theme was nominally ‘Beyond the Boundaries’ it could be argued this conference revealed just how much awareness, skill, and creativity is needed and how challenging it can be to identify ‘boundaries’ much less define them.

With speakers from such diverse locales (alphabetically) as Australia, Canada, Chile, China, England, Italy, Japan, and the USA, the perspectives were bound to be just as disparate. However, if there was a common thread running through the presentations it was activities and design ‘in sympathy with the natural (or local) landscape’ to borrow from the profile of Chilean landscape designer, Teresa Moller. She referred to the ‘essence and character of a place’ and ‘bringing nature closer to people’.

This course was set at the conference’s beginning by indigenous designer Alison Page whose creative practice ‘explores links between cultural identity, art, and the built environment’. As she explained, “anything built on country is an extension of country … responsive of/to country”.

Alison pointed out that perspective is expansive, depending on where we stand and, from an Aboriginal point of view, heavily involves the ‘locational principle’ referencing landmarks, vegetation, food and water sources, and seasonality.

“It’s not ‘nice to have’ it’s a ‘must have’”, she reinforced.

She explained how songlines carried the knowledge of the dreaming forward, and observed how hard it is in a throwaway society to ‘talk to’ items like family heirlooms, and how moving around country was so different from sedentary living. She then drew the links between design and storytelling, and how mimicry in art, design, and architecture can be motivating, engaging, and powerful.

The natural Australian landscape

In contrast to the indigenous way of living as part of the landscape, Prof. Andrew Campbell described how our industrial food systems have affected natural landscapes. He also pointed out that, because of their scale, they also give us a really big lever to pull to change things.

Prof. Campbell believes a lot of the current food security crisis, migration, and population movement, is structural with a lot of ‘unstable trends’ – for example rainfall not arriving when we needed it or planned for it.

In Australia (especially) the climate change story is in the temperature and rainfall variance NOT the averages; resilience to shocks is far more important, he advised.

He referred to the energy costs of irrigation and water movement, and commented: “if you’re not using gravity (then) you’re in the energy business”.

“There are converging insecurities. The landscape needs to be re-wired and re-plumbed. But we tend to replace rather than work with what’s here; we need to let floodplains be floodplains and estuaries be estuaries,” he commented.

“Landscape is where nature meets culture” he commented, and observed we are now ‘beyond ecological apartheid’ and are ‘socially constricted’.

He stressed “nor is it just about carbon!” He fears the emergence of a lot of “sub-prime carbon”.

Prof. Campbell pointed out that there has been much research, implementation, and success over years yet “policy amnesia, myopia and ad hockery” meant we are forgetting what we already knew, duplicating expenditure, and repeating past mistakes.

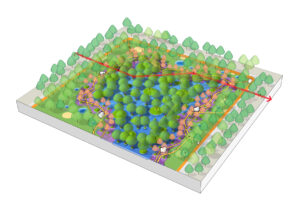

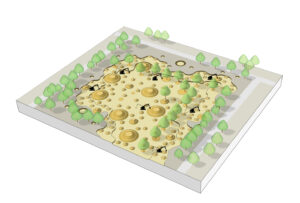

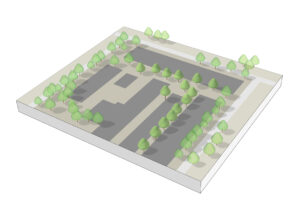

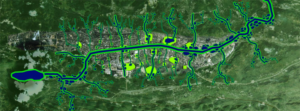

Above images: Quickly and easily transforming urbanised flood zones into beautiful immersive nature-based reserves (Images: Turenscape.com)

Healing the built environment

Prof. Konjian Yu, of Peking University (Beijing) and landscape company Turenscape, presented on a string of projects ‘healing the built environment’ and remedying the negative effects of past actions using nature-based solutions. The outcomes and turnaround times were impressive.

As many 20th century Australian projects saw urban water courses pipelined or channeled in attempts at ‘getting (flood) waters away quicker’ only to see flooding exacerbated in more recent times, China has also wrestled with the twin threats of the influence of a monsoon climate coupled with global climate change. Prof. Yu said more than 65% of Chinese cities are affected by inundation every year.

The response has been focused on a national ‘sponge cities’ project with Hainan’s Sanya Dong’an Wetland Park a model and proving ground. Rather than moving floodwaters on quickly, this approach slows water flows down, embracing the flood as a natural phenomenon. This is more effective than kneejerk reactions calling for ever higher levee banks, as many Australian localities would appreciate after last year’s extreme rain events.

As Prof. Yu observed, in the face of climate change and rising sea levels, all fixed infrastructure will become obsolete.

He explained how removing concrete walls and replacing them with resilient river banks, re-designing floodwalls on an ecological basis, using mangroves to replace hard barriers, restoring ‘sponge coast’ seawalls by lowering walls, and creating permeable ponding behind them can be highly effective at mitigating flood impacts.

Inspired by traditional Asian floating gardens these ideas adapt to variances in water levels, where perhaps two metres of water table variation can accommodate up to one million cubic metres of urban storm runoff!

In engineering terms most of these amendments are little more than simple and low-cost earthworks, replacing chronic flood zones with natural habitats, and public spaces with floating forests and artificial islands (often based on old concrete rubble) in ‘green ribbons’ of ‘beautiful immersive environments and nature-based reserves’.

These projects have provided replicable models of designed urban nature for regions with monsoon or variable climates that can address the multiple challenges of floods, habitat restoration and recreational demands.

Prof. Yu outlined how this has been done across China, and internationally, including Thailand. In most cases construction took little more than a year with landscape maturity in as little as two years.

While not re-engineering the natural environment to that degree, Melbourne’s City Architect Rob Adams has certainly overseen a re-engineering of the city’s streetscapes over several decades. At the Landscape Conference he summarised how the Melbourne Strategy Plan of 1985 has slowly, and subtly but surely maintained the city’s personality while supporting its economy, and increasing and enriching human activity (a pandemic notwithstanding).

He pointed out that “80% of the city’s public realm is made up of streets; design good streets and you design good cities”. An active movement ‘from grey to green’ began in the 1980s. Footpaths were quietly and gradually widened – a good foundation for subsequent retail and social interaction – especially with today’s café culture.

Rob Adams commented that ‘backyards’ (literally and figuratively via the greening and linking of public open spaces) are the new ‘green wedge’.

‘Feel’ more important than species

Later in the program Fergus Garrett, former gardener at Christopher Lloyd’s English manor house Great Dixter and now CEO of the Great Dixter Charitable Trust, expressed similar sentiments to those of Teresa Moller and Alison Page, including that ‘feel’ was more important than the plant species used.

Fergus recalled that he “didn’t want to be a gardener growing plants that don’t want to be there or that he didn’t want to plant”. He is proud that Great Dixter’s famous garden is regarded as the 25th most diverse in the United Kingdom and third in terms of number of species per square metre.

He has been described as taking “a minutely detailed, tactical approach to the aesthetics of plantsmanship” while he refers to “dynamic flora” and having a “hands off” approach, mimicing meadows that require very little maintenance. He admits they used to get letters of complaint from visitors about ‘weeds’.

“We need to loosen up aesthetically and understand what we’re doing,” he commented.

At Dixter we’re different, more like a garden nature reserve, he suggested, noting that ‘wildness’ does not necessarily mean biodiversity.

“We can blur the edges between horticulture and ecology while creating beautiful, artistic spaces. We need places where things can live, feed, and breed.”

While gardens are sometimes seen as part of the problem, they can be part of the solution, he commented.

About 10 years ago Fergus and the Great Dixter garden hosted Italian garden designer Luciano Giubbilei in a design residency. This association resumed in Melbourne, on the 2023 Landscape Conference’s program. Luciano’s early classic Tuscan influences were the movement of light – shade and reflection, textures of materials – stone and wood, and the stark atmospherics of black and white imagery.

Every element is important, he said. He found he could understand proportions – ordered lines and vistas. He was “totally comfortable in their simplicity”. However, as he travelled – to Morocco, the USA, UK (including Great Dixter and a show garden collaboration at the Chelsea Garden Show), and Spain, his design style changed as he learned more about plants. His designs became “more layered compositions with the addition of flowers”.

Luciano, who still sketches concepts by hand instead of using modern screen tools, progressed through several collaborations with artists, and commissioned designs before doing a garden in Tuscany and finding himself having come full circle in design terms. The Tuscan Garden featured mature trees and walls – “it had good existing bones”, he commented. Then it was on to his own project in Spain’s Balearic Islands and Raby Castle in the UK.

In an article in the Garden Design Journal (Society of Garden Designers) he was quoted: “I find that writing and recording information, and the sensations you have on site, is much more tangible when you get back than photographs.” However, studio work does start with cut outs and images, and creating a picture wall. “We work on a drawing board with pencils and go back and forth from the wall to the drawing board,” he explains. “You’ve already had an idea on site, so it’s just a matter of refining it. That’s the important part of recording things, because when you go back to the studio, things change. Features look very different on plan to when you were there.”

Streetscapes and creativity

In contrast to the sensitivities of ‘feel’ and the harsh realities of ‘climate’ and ‘natural landscape’, Canada’s Claude Cormier brought some ‘serious fun’ to landscape.

Where do landscape and art start and finish, or even merge? According to the blurb, Claude’s group CCxA “reinforces a practice of hybrids between design and art, nature and artifice, real and surreal … expanding into new hybrids of practice and collaboration, multiplying talents and insights towards new experiences and emerging solutions in the complex public landscape”. What it means is do not expect a conventional nature, or plant-based, project.

Instead, expect temporary or permanent, or moveable, installations and/or settings that can be extremely functional, or engaging, or completely whimsical.

“What is a garden? Do you need plants?” Claude asked. Let’s consider just three of those presented at the Melbourne conference.

Pink Balls: Along a socially and economically challenging narrow Montreal street, 170,000 plastic balls were suspended between the buildings five metres above the pavement. While simple, low cost, and easy to implement, the installation attracted surprising visitation and resulted in lifting the streets vibe and amenity. The idea was later expanded into a kilometre of ‘18 shades of gay’. The results were the same, only more so. Ultimately, even viewing platforms had to be erected to cater for the demand for selfies and Instagram postings. At the end of the installation, the balls were sold (for C$250,000!) and the money given back to other civic improvement projects.

Blue tree: In Sonoma (California, USA) a ‘blue tree’ appeared at the Cornerstone Festival of Gardens. The challenge was to ‘remove it’ without a chainsaw! The CCxA solution? Colour match 100,000 balls matching the sky behind and minimising the trunk. The attraction was taken down three years later at a cost of US$8000 for the balls and $7000 for installation. Bargain.

Sugar Beach: Take an old port area in Toronto on Lake Ontario. Restructure, add sand, umbrellas, lounges, boardwalks, and trees (with special accomodation for the rootzones) and voila – a new and desirable city lakeside attraction. All done in the CCxA manner – where does the art, the amenity, and the landscape begin or end?

Summing up

The Australian Landscape Conference, as introduced by convenor and MC Fleur Flanery, is aimed at “creating better places to live and work, sharing ideas and inspirations”. And as presenter Teresa Moller has said, “The potential for growth lies in erasing the barriers we have built between our sense of self and nature – to understand ourselves as part of it.

The recent presentations in Melbourne spanned the ‘landscape’ from indigenous links to country, across farming and land utilisation from a sustainable environment viewpoint, through the biodiversity of great non-traditional English gardens, the classic private and public landscape designs across the Northern Hemisphere, to the unpredictable(?) creativity of some French Canadians. The common thread? It’s a diverse and wonderful natural world under challenge. The challenges can be met with creativity, skill, experience, and the right attitudes.

Main photo: Beauty and productivity in Chile – vines, lavender for oil, and olives (Image: Chloe Humphreys)