Eyebright delight: Euphrasia in horticulture

Alex McLachlan

Many Australian Euphrasia species face declining populations due to significant changes in climate, with rising temperatures in Australia’s alpine regions putting Euphrasia populations at high risk. Botanic gardens are actively working to conserve some of the rarest species, however much work remains before euphrasia can be considered truly safe from extinction. Continued efforts are needed to ensure this stunning genus remains in the alpine landscape for future generations to enjoy.

Euphrasia, commonly known as eyebright, is a little-known yet striking genus. The genus was named after the happiness the flowers are believed to bring to those who see them, with ‘euphrasia’ translating to ‘joy’ or ‘gladness’ in Latin.

Euphrasia is a visually distinctive genus compared to most other Australian flora and is easily recognisable. The flowers are located terminally, with up to thirty flowers per spike, making them the tallest part of the plant. These flowers vary in colour, ranging from purple (the most common), pink, and white, to yellow, and even a mixture. The stems can range from purple to red, and the leaves are arranged opposite to each other and heavily toothed. Euphrasia is a cosmopolitan genus, found on all continents except Africa and Antarctica. They are hemi-parasitic, meaning they are partially self-sustaining as they photosynthesise on their own but require a host plant to siphon water and nutrients1.

Rare blooms

There are over two hundred species of Euphrasia worldwide, with twenty species found in Australia. While Euphrasia can be found in all states except the Northern Territory, many naturalists have yet to encounter these stunning plants. This is due to two main reasons. Firstly, Euphrasia is predominantly found in mountainous habitats and cool, moist climates. These plants typically reside within grasslands or open forests in sub-alpine or alpine ecosystems, with the easiest places to find eyebrights being along alpine walking tracks higher than 1,800m above sea level. Since alpine areas constitute less than one percent of Australia’s landmass, access to their habitats is limited for most people.

Secondly, of the twenty Euphrasia species in Australia, seventeen are listed by state and/or federal governments as vulnerable or worse (one species is currently recorded as extinct). Many of these threatened species are only found in a single location with fewer than 1,000 individuals. Unfortunately, due to climate change and human impacts, locating these beautiful plants is becoming increasingly difficult. Rising temperatures in Australia’s alpine regions put Euphrasia populations at high risk of declining populations2.

Horticultural difficulties

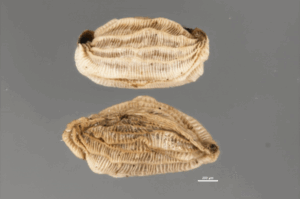

Although Euphrasia plants are attractive, they pose significant challenges for introduction to horticulture due to their semi-parasitic nature and difficulty in successful propagation. Trials conducted at the Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria, involving both cuttings and grafting, have been unsuccessful. Euphrasia plants are prolific seeders with each pollinated flower producing a pod containing up to 30 seeds. However, seed propagation is also complicated by a physiological dormancy, which requires cold stratification to alleviate this dormancy before germination can occur. Furthermore, it is currently unknown which host species Euphrasia parasitises, and more research is needed in this area before successful cultivation and propagation of Euphrasia species can be achieved.

Horticultural value

Commercial cultivation of euphrasia could make these striking plants readily available to the public, as they would make an excellent addition to any garden with their showy flowers and unique foliage. Additionally, eyebrights have a history of medicinal use3 dating3 back to ancient Greece, where they were crushed to extract a liquid and applied to treat various ailments such as conjunctivitis and eye inflammation. This medicinal use has contributed to their common name, ‘eyebright’. Additional research into propagation of Euphrasia may unlock its commercial potential.

Conservation horticulture

Conservation horticulture plays a vital role in addressing the increasing rarity of Euphrasia. Conducting research to better understand seed dormancy, germination responses, and parasitic tendencies can facilitate the development of ex-situ collections. These collections are essential for safeguarding threatened species from natural disasters and preserving genetic diversity. Additionally, ex-situ collections enable the enhancement of genetic variation through controlled hand pollinations between populations that would not naturally interbreed in the wild. Ex-situ collections also provide opportunities for reintroducing rare eyebright species, thereby reducing the risk of extinction.

Concluding remarks

While many Australian Euphrasia species face declining populations due to climate change, botanic gardens are actively working to conserve some of the rarest species. However, much work remains before Euphrasia can be considered truly safe from extinction. Continued efforts are necessary to ensure that this genus continues to add vibrant colour to the alpine landscapes for future generations to enjoy.

References

- Svensson, B. M., & Carlsson, B. Å. (2005). How can we protect rare hemiparasitic plants? Early-flowering taxa of Euphrasia and Rhinanthus on the Baltic island of Gotland. Folia Geobotanica, 40, 261–272.

- Zlonis, K. J., & Gross, B. L. (2018). Genetic structure, diversity, and hybridization in populations of the rare arctic relict Euphrasia hudsoniana (Orobanchaceae) and its invasive congener Euphrasia stricta. Conservation Genetics, 19, 43–55.

- Paduch, R., Woźniak, A., Niedziela, P., & Rejdak, R. (2014). Assessment of eyebright (Euphrasia officinalis L.) extract activity in relation to human corneal cells using in vitro tests. Balkan Medical Journal, 2014(1), 29–36.