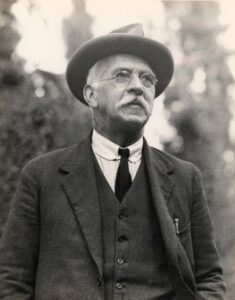

The man who planted Canberra

By Gabrielle Stannus

Many of us would remember learning in school about the pivotal role that American Walter Burley Griffin played in the design and development of the Australian national capital. However, author Robert Macklin says that another man deserves more credit for his role in transforming the Limestone Plains into the thriving garden city we now know as Canberra, and for laying the foundations for modern Australian horticulture. That man is Charles Weston, an English-born horticulturist, whose life and career Macklin has mapped out in his new book, The man who planted Canberra.

Robert Macklin has had an extensive and varied career including a stint as a jackaroo. His writing career started when he became a cadet journalist with the Courier Mail in Queensland. He then joined The Age’s press bureau in Canberra, before being offered and accepting the opportunity to become Press Secretary to John McEwen, Australia’s Deputy Prime Minister at the time. Only three weeks later, then Prime Minister Harold Holt took his fatal swim at Portsea, resulting in McEwen becoming the country’s leader with Macklin his prime ministerial Press Secretary. One would think that Macklin has many stories to tell about this period in the capital’s political history. However, it was another story that grabbed his attention, one still tinged with political intrigue, but with a horticultural twist.

Early in 2023, members of the Canberra and Region Heritage Researchers approached Macklin with a proposal to use a thesis developed by the late John Gray as the foundation for a biography of Charles Weston, a horticulturist whose work left a legacy on the nation’s capital. In 1998, Gray, a forester and landscape designer, completed a doctoral thesis on Weston’s afforestation of the national capital during its formative years. Macklin says that this was a labour of love for Gray, one he had postponed until his retirement from Canberra’s National Capital Development Commission. For years, Gray had been frustrated that Weston’s achievements had been eclipsed by the credit bestowed almost exclusively upon the American designer Walter Burley Griffin and his wife, Marion Mahoney Griffin.

After initial research, Macklin agreed to write Weston’s biography, fleshing out Gray’s thesis to include the discussion of the national and international forces that moulded and shaped the nascent Australian capital, and laid its foundations as one of this country’s premier garden cities. ‘I could see that the book required a much broader scene. While making Weston the centrepiece of the book, the story is of Canberra’s early days,’ says Macklin, ‘And it makes for a ripper yarn, to which we were able to bring to it a great deal about the horticultural and the arboreal side of our great city. To my surprise, this side has really grabbed hold of people’s imagination. It is just amazing the number of people who are extraordinarily interested in this world.’

Charles Weston was born in 1866 in a hamlet called Poyle, to the north of London, in England. His parents supplemented the family’s meagre income and food through gardening, fostering a love in young Charles for horticultural pursuits. When he was 13, Weston secured a position as a gardening apprentice at Poyle Manor, before later completing his apprenticeship at Ditton Park, whose layout had been transformed by Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown in the 1760s. He was then transferred to Drumlanrig Castle in the Scottish borderlands, where he was taken under the wing of David Thomson, one of Britain’s most influential head gardeners at the time. ‘At Drumlanrig, Weston went all the way up to the very top of the gardening industry in Britain, no mean feat for someone who did not have a degree. With the British class system, it really meant that he had reached the limit of how far he could go in his career,’ says Macklin.

‘In 1896, Weston chose to emigrate to Australia. There was talk of Australia becoming federated. I believe that even then, he had his eye on the building of Canberra. Certainly when Weston got to Australia, he was able to watch the comings and goings of the Parliament in making the choice of where the new national capital should be located. However, Weston quickly realized that, unlike in England, there was no opportunity for him to work at his level in the private industry, it had to be in the larger public industry. In fact, he got his first real start in Australia with the Sydney Botanic Gardens. He became very great friends with Joseph Maiden, who was the superintendent there. Maiden had the power and the academic qualifications that Weston lacked, but together they were a force.’

Maiden promoted Weston to the role of head gardener at Wotonga, better known as Admiralty House, a location now known for Kirribilli House, the official Sydney residence of the Australian Governor-General. Weston became a member of the Horticultural Society of New South Wales and a frequent exhibitor at horticultural society shows in Sydney; he developed five hybrid Watsonia species, some of which were named after the admirals’ wives. But while the combination of work and family time in beautiful surroundings had great appeal, Macklin says that Weston had not spent all those years of training in the great estates of the United Kingdom to remain essentially a house gardener in Australia. He then became Head Gardener of Federal Government House in Sydney before being promoted to superintendent of the State Nursery at Campbelltown, a position he held from 1912-13. During that time, the Federal Government also sought out Weston’s advice about a possible nursery at the site of the new capital.

The same week that Weston first arrived at what we now know as Canberra in April 1911, the Australian government announced a worldwide competition for the design of its national capital. American Walter Burley Griffin eventually ‘won’ this competition, aided in his design by his wife Marion Mahoney Griffin. Burley Griffin was appointed Federal Capital Director of Design and Construction by Prime Minister Cook in October 1913. In the meantime, Weston had been formally appointed in January 1913 as officer-in-charge of the Afforestation Branch of the Federal Capital Commission.

Macklin says that Griffin had no firm plans in his competitive design for afforestation or horticultural elements in the city, despite holding a landscape architect’s qualification. Weston did though, creating a master plan for his dream city. Macklin says that Weston was a leader of the Garden City movement along with Maiden in Australia: ‘This movement had its beginnings in Bourneville in England. They brought it to Australia; Maiden used Darcyville, a Sydney suburb, and Weston used Lithgow, as areas to demonstrate the Garden City concept, whilst Weston was working on the national capital itself. The national capital to Weston’s mind was a huge step forward in the way that people thought about city planning.’

‘The outbreak of the Great War in 1914 slowed progress of the capital’s development, as did a Royal Commission into the battle between Walter Burley Griffin and the Home Affairs department in 1916. At the same time, Weston was reafforesting the whole area around Canberra, which had been absolutely destroyed by the settlers who had chopped down all the trees and introduced rabbits. The place was a mess. Clearly Weston saw that as his first most important job.’

Weston’s first plantings included Pinus insignis (now P. radiata, Monterey pine), Cupressus macrocarpa (Monterey cypress) and other seeds and plants from suppliers and nurseries overseas. He also secured lists of local plants, including prevalent weeds. His planting lists for experimental trials included species useful for shade and shelter, food and fodder, as well as the beautiful and ornamental1.

Macklin says that Weston decided that he would take species of trees and shrubs from all around the world: ‘His thinking was that in simple terms “we do not want shade in Canberra in the wintertime, but we do want it in the summertime”, so a mix of deciduous and native trees and shrubs were the only way to go. However, before making the choice, he put the nursery and the species through scientific trials, literally hundreds of trees and shrubs were tested at his Acton nursery. He had also developed a great arboretum known as Westbourne Woods in Yarralumla that swept right across to the other side of the lake. Those were the two areas, where he did all his scientific work and his records in his own writing remain there.’

Burley Griffin did not think well of some of Weston’s work, taking issue with the latter’s placement of the nursery at Yarralumla. The Royal Commission’s report reinstated Griffin’s design but relegated the cork oak plantation ordered by Griffin to an experimental stage, whilst Weston’s nursery and his Westbourne Woods arboretum remained intact.

Weston continued his afforestation works apace, says Macklin: ‘Weston first concentrated upon this strange building, which could have been designed or created by H.G. Wells. It was a silver helmet on the top of what we now call Mount Stromlo. It was the Stromlo Observatory. As a scientist, Weston was really engaged by the idea of having this wonderful aspect right there in Canberra. He wanted to make the best of it for the astronomers. So, he planted almost one million trees all the way up Mount Stromlo, to make life easier for them, to stop the dust and give them a good break to look at the sky.

‘He also developed material for a brickworks, because bricks were going to be needed for the building of Canberra. That required a particular kind of ground, which he wanted to plant out after he extracted it. It was a big shale area, and he used gelignite to bust the soil up. Weston found to his surprise that the explosions improved the capacity of the nearby soil to nurture the plantings. It was one of Weston’s ‘contributions’ to horticulture in this area!’

Weston was promoted to Superintendent of a reorganised Parks and Gardens Branch in 1920, and at that time was in a rush to finish his work as Parliament House was due to be opened in 1927. According to Macklin, the entry to this building was of great importance in Weston’s planning for this site and planting there needed to make a statement: ‘The trees had to be quite big to be transplanted there. They were mostly poplars. Weston grew them to a height of about eight to nine feet tall. He then moved them from the nursery to Parliament House in a rattle trap operation, with three horses pulling a cart with these trees stuck up at the back. Once planted, every single tree took, and he had no failures.’

Weston retired at the age of 60 in December 1926, only a few months before Parliament House was officially opened in May 1927. By that time, he had successfully executed 50 planning projects in nine different zones in the new capital city, planting over three million trees and shrubs after rigorous testing and experimentation. He died in 1935, and his cremated ashes were scattered in the Parliament House gardens, along with those of his wife Minimia, who died in 1937, the only occasions when such an honour has been granted.

A.E. Bruce and John Hobday followed in Weston’s footsteps, continuing his work until Lindsay Pryor took over as superintendent of Parks and Gardens in 1944. ‘Pryor reactivated Weston’s experimental programs and in 1945 he founded the Herbarium of the future Australian National Botanic Gardens and began work on the gardens themselves. While maintaining Weston’s approach to species selection, Pryor concentrated on improving the quality of the exotic and indigenous plants he used in landscaping. He did make some changes to Weston’s approach to make greater use of eucalypts in Canberra’s main avenues. He also shifted to a more informal approach to landscape design than Weston,’ says Macklin.

Whilst their fellow Australians have mostly forgotten the works of Weston, Canberrans have honoured his legacy. Burley Griffin’s name was given to the lake created at the front of the original Parliament House; however, Weston’s name was commemorated in a creek, a street and a district in Canberra2. He is also honoured in the name Eucalyptus westonii Maiden & Blakely (1928), for which he collected the type2, a reputed hybrid of E. goniocalyx × E. mannifera3. Every second Sunday, visitors to the national capital can take a guided tour of the Westbourne Woods arboretum, which Pryor turned into the 18-hole Royal Canberra Golf Course, where they can see those of Weston’s trees which still remain.

However, Macklin says that Weston’s legacy to Canberrans is more enduring than these honours: ‘His planning of species was very much an advance in horticulture, the way he was so meticulous in his planting. He invented this system of planting young trees in circles of five or seven to see how they would respond to wind, soil and rain. These days you can always tell a Weston development in Canberra by these circles of trees. In this time of climate change, we are in a good position in Canberra compared to other cities like Melbourne and Sydney, because we have a huge diversity of species planted in our landscapes. Some of these trees and shrubs will like a warming area.’

Without realising it at the time, Weston created a garden city likely to adapt and evolve to the impacts of anthropogenic climate change. Now, in my view, that is a legacy indeed!

References

- Coltheart, Leonore. (2011, December). Nursery Tales for a Garden City: The Historical Context of the Records at Canberra’s Yarralumla Nursery. A report for the Australian Garden History Society (ACT, Monaro & Riverina Branch).

- Australian National Herbarium. (2025, February 9). Weston, Thomas Charles George (1866 – 1935). https://www.anbg.gov.au/biography/weston-thomas-charles-george.html

- Centre for Australian National Biodiversity Research (2020). Eucalyptus Species > W. EUCLID. Retrieved August 18, 2025, from https://apps.lucidcentral.org/euclid/text/entities/names/Species_list_Eucalyptus_w.htm

Gabrielle Stannus

Inwardout Studio

M: 0400 431 277

E: gabrielle@inwardoutstudio.com