The intelligent canopy: How AI Is changing urban greening

By Michael Casey

As artificial intelligence moves into city planning and landscape design, a new partnership is emerging between data and horticulture.

Artificial intelligence is a phrase that can sound cold and mechanical, far removed from the soil, roots and living systems we are all accustomed to. Yet in truth, it is already shaping how we plan, build and care for the green infrastructure that keeps our cities liveable. What makes this shift interesting is not that computers are taking over design, but that they are helping us see and manage the natural systems we rely on with far greater clarity. The same way a good horticulturist learns from the signals of plants and weather, AI learns from patterns in data and, when used wisely, it can help us respond faster, waste less and design more resilient landscapes.

For decades, the horticultural profession has relied on experience and observation to guide decisions. We have walked sites, checked moisture levels by hand, watched plant responses through the seasons, and adjusted our methods over time. That instinct and professional ability will never lose value, but as cities grow denser and climates grow harsher, the scale of what we manage has outpaced our capacity to monitor it manually. Urban heat, water scarcity and biodiversity loss now demand tools that can interpret thousands of small signals at once, such as canopy temperatures, substrate moisture, rainfall patterns, and even pedestrian movement. AI does not replace human judgement but simply extends it, giving us another lens to interpret the living systems we nurture.

Take the example of tree canopy mapping. Only a decade ago, city councils would commission costly aerial surveys every few years to estimate shade cover and heat exposure. By the time the results were compiled, they were already outdated. Today, machine-learning programs can read satellite and aerial images to estimate canopy cover down to the street level in near real time. Platforms such as Google’s Tree Canopy or Melbourne’s own Urban Forest Visual make it possible to identify which suburbs are missing shade, where trees are declining, and which streets would benefit most from new planting. That data allows councils to target resources where cooling and comfort will have the greatest impact for people which is a far cry from the data collection of the past. The same methods are being used internationally with the World Resources Institute and Meta recently developing an AI model that maps individual trees outside forests, helping cities and landowners account for the green assets that were once invisible to large datasets.

This intelligence is now moving up onto rooftops and into façades. Green roofs were once fairly static systems with a fixed soil depth, a timer-controlled irrigation line and the hope that the plant mix would survive summer heat. Today, the emerging generation of ‘smart’ roofs acts more like responsive ecosystems. Some examples of new design techniques for roofs describes how sensors embedded in the substrate and canopy feed real-time data on temperature, humidity, moisture and light into small AI controllers that automatically adjust water delivery or drainage. The roof becomes a living, learning system, able to anticipate weather events and fine-tune its own performance. In a country like Australia, where rainfall is unreliable and evaporation extreme, that kind of predictive irrigation could make a huge difference, not only in saving water but in protecting plant health through periods of heat stress. It transforms a green roof from a decorative layer into an active piece of climate infrastructure.

Across the world, digital design platforms are also evolving to bring these insights into early-stage planning. Programs like ArcGIS Urban and Digital Blue Foam allow designers to model entire precincts in three dimensions, combining building forms with vegetation, surface materials and climatic data to simulate how different layouts affect temperature, runoff and comfort. They use AI to test scenarios such as ‘what if this roof garden doubled its soil depth?’, or ‘what if more trees were added along a pedestrian corridor?’. For practitioners like us, these tools provide a virtual prototype of the site before a single plant is installed. They make it easier to quantify what we intuitively have always known; that a well-placed tree can reduce surface temperature by several degrees, or that a layer of planting can turn a hard roof into a cooling sponge.

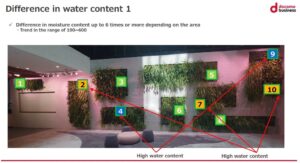

At the same time, AI is finding its way into maintenance and monitoring. The HYVERT system in the United Kingdom, for example, links sensors, irrigation valves and cameras on living walls to a central dashboard that adjusts watering and alerts maintenance teams before plants begin to fail. Similar approaches could easily apply to our Australian podium landscapes or green facades. Even simple moisture and temperature sensors connected to a cloud-based dashboard can give site managers a live view of plant health, helping reduce water waste and plant loss. Pair those readings with drone imagery or fixed cameras, and you have a powerful maintenance map showing which zones need attention long before problems become visible from the ground. However, none of this replaces the horticulturist’s skill, it simply provides better information to support timely, targeted action.

What makes this shift so interesting is how these individual technologies can link together. When roofs, streetscapes and green facades share data, they start to operate as an intelligent network, more like a ‘cognitive canopy’ that senses and responds to changing urban conditions. Stormwater volumes, surface temperatures and plant stress levels can all feed into shared dashboards, helping councils coordinate cooling, flooding control and maintenance across entire precincts. This connected-system thinking is what turns isolated green assets into genuine urban infrastructure capable of delivering measurable ecosystem services at scale.

Of course, as with any new tool, there are risks. The same AI that helps us optimise irrigation could also push designs toward narrow efficiency goals if we are not careful. If the algorithm values only water savings, we might lose biodiversity or seasonal character by selecting a limited range of species. If the data that trains the model is skewed toward wealthier suburbs, investment could follow that bias, leaving hotter, lower-income areas behind. This scenario outlines two possible futures, one of ‘ascend’, where AI and nature collaborate to create diverse, inclusive and adaptive cities, and another of ‘atrophy’, where automation and monoculture replace stewardship and local knowledge. The difference between those futures lies in governance and intent. Technology may be neutral but the values we embed in it are not.

That is why horticulturists and designers remain central to this conversation. We bring the ecological understanding, the sense of place, and the respect for living systems that no algorithm can replicate. AI can crunch millions of data points, but it cannot feel the texture of soil or read the subtle cues of plant stress on a summer afternoon. The best results come when digital and natural intelligence work together; when the data confirms what our experience already tells us, and when our judgement corrects the blind spots of the machine. In practice this means starting small. Use canopy and heat-mapping tools to prioritise shade, test predictive irrigation on one pilot roof, integrate basic sensors into maintenance plans, and share that data openly with clients and councils. These small steps gradually build a culture of evidence-based horticulture that still honours craft and care. AI will not plant a single tree, but it will help us choose the right tree for the right place and keep it thriving long enough to make a difference.

If the past decade was about proving that green infrastructure works, the next decade will be about making it smarter, fairer and more resilient. As long as we keep people and plants at the centre of that conversation, the intelligent canopy will grow stronger with every new project we plant.

Michael Casey

Director, Evergreen Infrastructure

Company Director, Australasian Green Infrastructure Network

Technical Panel, AIPH World Green Cities Awards

World Ambassador for World Green Roofs Day

E: michael@evergreeninfrastructure.com.au