Aquatic greenlife reduces bovine greenhouse gases

By Karen Smith

What if you could take a waste by-product of your normal production process and turn it into an income stream, and at the same time reduce your carbon footprint? Collaboration between the University of Technology and Sydney brewers, Young Henry’s, are investigating the link between the diet of cattle and the greenhouse gas emissions they produce.

I know that the nursery and garden industry generally sees itself on the good side of the CO2 equation and growing green life is a positive method for reducing one type of greenhouse gas. Brewing beer historically was one way of taking green life and releasing the carbon dioxide (CO2) back into the atmosphere, putting it on the other side.

A chance meeting between Richard Adamson from Young Henrys and Prof Peter Ralph from UTS Climate Change Cluster, alerted Richard to a possible technological partnership. Brewers’ spent grain is often used as a food source for the dairy and beef industry. This represents a sensible use of a waste product that would otherwise have to find a home somewhere. Unfortunately, brewing contributes to greenhouse gas emissions by releasing CO2 from production directly to the atmosphere, and inadvertently by the methane emissions of cattle called methanogenesis.

Researchers around the world and at UTS were investigating the effect of a strain of algae or seaweed called Asparagopsis on the emissions caused by cattle, with amazing results. Research indicated that introducing small amounts of algae into the diet of cattle reduced emissions by large amounts.

Innovators at Young Henrys Brewery saw that they could use the growth of macro algae to enrich the spent grain used for livestock feed. Not only could the enriched grain be a value add to the business, but the process of growing algae was a perfect use for the CO2 that would otherwise vent to the atmosphere.

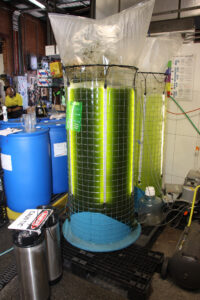

Investing some capital in a prototype production process allowed brewers to capture the CO2 and use it in the brewing process, saving a considerable amount of money by not having to buy the gas used for carbonation. The excess CO2 captured is then fed into a ‘bio-reactor’ to grow algae. Algae uses photosynthesis to convert CO2 to carbon and oxygen.

Finding the right strain of algae, is where researchers are at the moment. Algae food supplements can be found anywhere that dietary supplements are sold. The algae for minimising methanogenesis are not the same as those found on supermarket shelves. A company in Tasmania called Sea Forest, is cultivating Asparagopsis in marine farms for use in cattle feed for this purpose.

The UTS team and Young Henrys are hoping to find better strains of algae, by bioprospecting in the wild and by selective breeding to develop a super-strain. That should sound familiar to many in the nursery and garden industry. The many species of algae have to be tested under the unique growing conditions found in the bioreactors and shown to be effective as cattle feed. Additives to cattle feed must show they do not degrade the quality of the dairy or beef, nor distort the taste.

Like any plant, algae require light and nutrients. The selected algae are taken from a small sample, propagated and checked, making sure it is clean and contamination-free. It is then added to 200 litre tanks where CO2 is bubbled through continuously. Artificial lighting is supplied by LED technology at a cost to the efficiency of the system. Future improvements to the system, foreshadowed by Richard Adamson, would see more natural light used when possible, reducing the reliance on artificial systems. Currently, the 200 litre bioreactors at Young Henrys have a planting to harvest time of about one month.

Richard is optimistic about this process and believes it is scalable. He envisages a time when large breweries worldwide could embrace this technology. He also believes that nursery wastewater could grow harvestable algae. A question unanswered at the moment is what will happen to the carbon price. Some Australian companies are seeking ways to reduce their carbon footprint by buying credits from companies that can offset carbon production and Young Henrys see their investment as a step in the right direction.