Designing resilient plant communities

By John Fitzsimmons

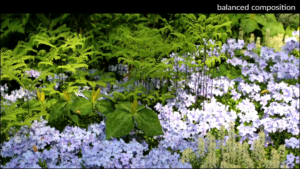

Plant communities or mixed plantings, whatever you call them, are incredibly popular right now. It’s exciting seeing the work being done to show the public just what’s possible – evocative, romantic, instead of the block plantings or module-based plantings often used. But this means underpinning the garden’s emotion and aesthetic with science, as Phytolab’s Claudia West explained at the recent Australian Landscape Conference.

Claudia explained some of the methods of designing plant communities and how to avoid some of the common mistakes. She expressed alarm at the number of plant communities being installed that fail.

The first year after installation, things often still look great. A lot of flowers, a lot of biodiversity, and things seem to be developing in the right direction, but unfortunately a lot of projects in their second and third years start to turn, and mixed plantings are getting bad reputations from a really large number of systems that don’t evolve in the direction originally envisaged or intended, she observed.

Claudia used the example of a US convention centre roof where, shortly after planting, the plants decided to do something completely different to what the design team envisaged. Putting a few annual flowers in front does not hide the big beast in the background if they are not correctly designed or managed, and it can quickly become beyond repair and simply has to be taken out and started again.

Claudia said there is no denying designed plant communities are incredibly complex, even if they consist of just a few different species. Many designers are overwhelmed putting so many plants together in stable compositions.

“As soon as ‘natural dynamics’ are allowed, it can become difficult to predict how a planting will perform long term, and how stable it will be in the coming decades. Luckily, there is research available to us into how plants interact with one another. Out of this research we can extract certain design models that can help us solve this problem of stability and how to arrange species in more stable compositions.”

She referred to research from people including Richard Hansen, Friedrich Stahl and Hermann Mussel who worked at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) Weihenstephan School for Landscape Architecture and Garden Design at Freising. Hansen worked on the behaviours between plants, especially herbaceous plants, that resulted in a ‘thinking model’, that allows designers to make better decisions about what kind of behaviour to place where within a layered system of designed plant communities. (Hansen, R and Stahl, F, 1993, Perennials and their garden habitats (English), Timber Press).

This describes ‘the levels of sociability of plants’ – the competitiveness of perennial plants. It describes five categories based on how competitive they are with other plants.

Level I: Species that usually exist as singles or very small clusters (1,2 or 3 at a time). They tend to be long lived, non-spreading, not clonal, and don’t recede much, with some as old as trees.

Level 2: Perennials that naturally occur in slightly bigger groupings (about 3 to 10). They are also pretty long lived but usually a bit more dynamic, starting to show some clonal spreading behaviours.

Level 3: Plant species that occur in even larger groups. They are more social with others of their own kind, in groups of about 10 to 20.

Level 4: Even more aggressive species, usually in even bigger clusters.

Level 5: The ‘bullies of the plant world’ that love to be surrounded by more of their own kind and make really large colonies in wild plant communities. They can be dominant and even ‘choke out’ competitors.

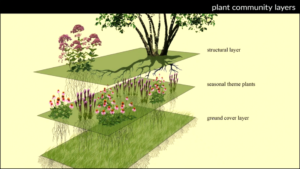

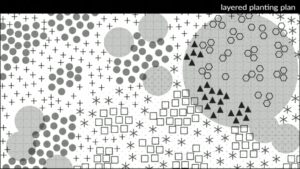

Using this knowledge, the first approach is to divide the plant community into spatial layers inspired by how plants layer in wild ecosystems, which can have distinct layers with ground covering species right at the base of the soil and then taller plants, emerging species, reaching out over the top of this ground matrix towards the sunlight.

“This is a simplification of something that is very more complex in the wild, but it can help us build a designed plant community in a simplified way by applying some of this layering strategy,” Claudia commented.

“The ground layer at the bottom is really the carpet, or backing, which ties all the layers together. The structural plants on top are the big elements that provide garden spaces, like woody plants or tall perennials, that frame spaces or hide infrastructure we don’t want to see. In the middle we have seasonal theme plants that provide spectacular colour events in designs and make them emotional.”

“So, designed plant communities usually have all three layers but sometimes they don’t have the structural layer, e.g. where we want open sight lines or there are height restrictions, but the ground layer and the seasonal theme layer are usually present in designed plant communities.”

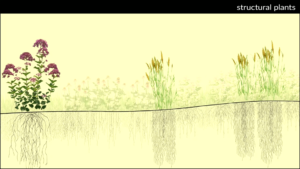

While the structural plants really hover over the lower layers, their roots are often much deeper ,and are not in direct competition with those of the groundcover species and the seasonal theme plants.

Many typical structural plants used in these designs are perennial clump-forming grasses with a typical vase shape, and they nearly all have ‘naked feet’ with very few leaves at the base of the plant. In the wild ecosystems in which they evolved, there would be other plants growing right there at their feet, so they often evolved leaves above their competitors to not be in direct competition for sunlight.

In the mixed middle layer, we often have very colourful ‘show stopper – eye candy’ species that, when in bloom, create seasonal moments erupting out of the mid-layer.

In a typical system, we don’t have bark or gravel mulch but ground covering species that are compatible with these other layers, covering the soil, preventing erosion, and preventing weeds that would otherwise appear. They are the glue that holds it all together, said Claudia.

The challenge is to select the right kind of species for these three basic layers, to keep the planting stable so the ground layer doesn’t out-compete everybody else, and so certain important structural or seasonal theme plants don’t disappear in the first five years.

Some species appear to have the form/morphology for a structural application BUT they may actually be Level 4 and quickly colonise the planting and large areas, i.e. the right appearance but the wrong behaviour. Levels of sociability are as important as form. Other species’ sociability can also become apparent, re-seeding prolifically and spreading beyond the original planting. They can ‘get out of hand’ and surprise designers.

For seasonal theme plants in the mid-layer, a higher level of sociability (Level 2 and 3) is usually helpful. If they seed a bit more, it makes the theme stronger but are great structural plants that are strongly clonal and can make really large colonies over time.

For groundcovers, use Level 4 and 5 plants that are naturally more dynamic, that either re-seed a lot more, or are more clonal, knitting pieces together and filling the gaps. They can also require fewer plants at the beginning which can reduce the project cost.

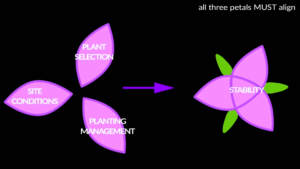

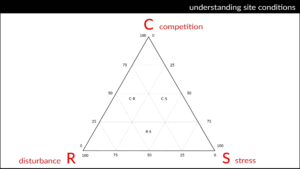

When designing plantings, we usually consider the ‘three petals’, site conditions, plant selection and site management, Claudia said. However, to ensure stability we need to go further. For this she referred to the late Prof. J Philip Grime’s (1935-2021) work on plant ecology, the ‘CSR’ strategy. This has been around for decades, Claudia pointed out, and is often used more in ecology but is incredibly useful for planting designers as well.

It digs deeper into analysing, and understanding, site conditions, dividing plants and habitat types, into a three-way trade-off between Competition (C) Stress and (S) Disturbance (D or R). No plant or organism can do all equally well at the same time. They either evolved or became adapted to tolerate stress, or they can handle disturbance.

“If one species falls out of line, these systems can become unstable and quickly fail. Only if all three petals align, do we get some semblance of stability,” Claudia said.

At this point, plant and site management become important. Example: There is normally very little ‘disturbance’ up on a green roof. It’s very dry, often windy, with high UV and shallow or poor soil/growing media, but if someone decides it’s too dry and turns the water on, or a drain gets blocked, the ‘environment’ becomes ‘better’, more competitive, and the plant palette/mix will also change in response. More competitive species in the mix will start getting the upper hand because the conditions are now more beneficial to them! The stress tolerators will be reduced or disappear entirely. The three petals fall out of alignment.

Observe – the plants never lie! Claudia pointed out.

Designed plant communities are still “new territory”. The plans are also so different from the familiar block plantings – very complex, she commented. They need different methods, new perspectives and deeper relationships with growers and nursery suppliers.

“Those working with designed plant communities are painfully aware that there are very few species available in the trade right now, to fill all these niches that we need plants for in these designs. So, we constantly work with nurseries to custom-grow species that are missing, and expand the palette to produce these planting systems, not just relying on the ‘eye candy plants’ or the typical new cultivars that are available, but also to show nurseries that there is a market for other more functional plants that are very much a part of successful plant communities. We are also working with those doing the seed collection, division, sourcing etc., basically helping to build an industry that supports more complex planting design.”

“Often what is available in a traditional horticultural plant nursery is not giving us all the tools we need to do our work correctly.”

“These plantings don’t just happen. It really takes a team and good communication, using every project as an epicentre for change,” Claudia said.