Pollination at night

By Denis Crawford

The value of night pollinating insects has long been overlooked, but recent studies show just how important nocturnal insects are for horticultural production.

Information about crop pollination is nearly always dominated by the European honey bee (Apis mellifera) and how vital that particular insect is to the food that we eat. I’ve written on several occasions how other pollinators, including native insects, are just as significant for crop pollination. However, most of these pollinators are active during the day (i.e. diurnal), so what happens when the sun sets?

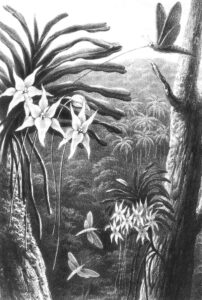

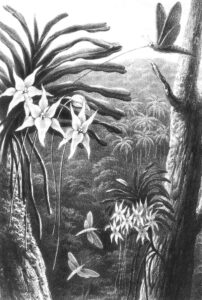

Leaving aside bats and possums etc., the obvious night-shift candidates are moths. A famous example is Darwin’s hawk moth Xanthopan morganii praedicta. On the 25th of January 1862 Charles Darwin received a box of orchids from James Bateman, a well-known orchid grower. The package included the long-spurred orchid Angraecum sesquipedale, anepiphytic orchid native to the lowlands of Madagascar.

The spur (nectary) of Angraecum sesquipedale amazed Darwin. In a letter to Sir Joseph Hooker (Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew), Darwin wrote, “I have just received such a box full from Mr Bateman with the astounding Angraecum sesquipedalia [sic] with a nectary a foot long. Good Heavens what insect can suck it?” In another letter to Hooker he wrote, “In Madagascar there must be moths with proboscides capable of extension to a length of between ten and eleven inches!”

Darwin was right of course and eventually a moth, Xanthopan morganii praedicta, was collected in Madagascar with a suitably long tongue, but it took until 1903. The specimen found had a wingspan of about 16cm and a tongue length greater than 20cm. Direct observations and photography of the moth feeding from the flowers of Angraecum sesquipedale came even later, in1993.

Darwin cited the flower of Angraecum sesquipedale and his predicted long-tongued moth as an example of coevolution. His theory was supported by another giant of science, Alfred Russel Wallace. The theory was that the flower and the moth evolved together in a way that was mutually beneficial. This theory has since been disputed (Jermy, 1999), “Deep flowers are for long tongues otherwise such flowers could not exist. Long tongues are not for deep flowers, as feeding with long tongues is also possible in shallow flowers. Great flower depth is the result of one-sided plant adaptive evolution, which is more plausible than coevolution explaining the origin of this plant-pollinator relationship.”

The new theory goes like this: Moths evolved long tongues as a way of avoiding being eaten by predators, such as spiders, waiting on the flowers. With a long tongue, a moth can reach the nectar in a flower with a short spur without coming too close to the flower (and being eaten). Unfortunately for the flower, the moth doesn’t pick up any pollen in this case so pollination doesn’t occur. If the plant evolves to have a flower with a longer spur, the moth has to move in a lot closer to reach the nectar and will most likely come in contact with pollen. Some moths may be eaten by spiders but enough moths will successfully pollinate some flowers and so both species survive.

(Supplied by Denis Crawford of Graphic Science)

The fragrance of the long-spurred orchid Angraecum sesquipedale is produced during the evening and night, making it attractive to night pollinators like Darwin’s moth. Other plants, like night-blooming cacti, make sure they are visited by nocturnal creatures like bats and moths by only opening at night. Most other plants, including horticultural crops, are pollinated by a combination of insects during the day and nocturnal insects at night. There have been a number of studies on the role of night pollinators in natural ecosystems, but relatively very few studies on the contribution of nocturnal pollinators to crop production.

There is growing evidence that suggests nocturnal insects are more important as pollinators of crops than previously believed, and they are not just moths. Studies of night pollination of lowbush blueberry, Vaccinium angustifolium, has shown that a number of fly families, and some beetles, as well as moths, are drawn to flowering blueberry bushes at night. The fly family that seemed to be the most significant pollinator was Tachinidae. Flies of this family are well known for being very bristly, which enables them to pick up pollen more readily than smooth bodied insects. Tachinid flies are also parasitoids of other insects, which makes them doubly beneficial.

(Supplied by Denis Crawford of Graphic Science)

The moths identified in the blueberry study were dominated by species in two families, Geometridae and Noctuidae. This is not surprising given that they are the two most species-rich moth families. Beetles were dominated by species in the weevil family Curculionidae, and many species of this family are well known for being active at night.

A recent study (Robertson et al, 2021) in Arkansas, U.S.A, shows that nocturnal pollinators make a significant contribution to apple production. The most commonly observed insects visiting apple flowers at night were moths of the family Noctuidae, with the two most common species being true armyworm (Mythimna unipuncta) and variegated cutworm (Peridroma saucia). Interestingly, the larvae of these two moths are significant pests in other crops such as grain crops and vegetables. It goes to show that insect-plant interactions are anything but simple.

The talk about insect decline around the world has also made us think about the decline in pollination services in both cultivated plants and natural ecosystems. We need to be including the night pollinators in these discussions. A study carried out a few years ago (Knop et al, 2017) shows that nocturnal pollinators have a unique hazard to contend with, light pollution. The study showed that nocturnal visits to plants were reduced by more than 60 percent in areas with artificial illumination compared to areas that were not illuminated artificially. It would be a shame to drive away all the night pollinators before we identify them and the plants they pollinate.

Main photo: An illustration of Darwin’s hawk moth feeding on Angraecum sesquipedale (Supplied by Denis Crawford of Graphic Science)

References:

Jermy T. 1999.Deep flowers for long tongues: a final word. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 14: 34.

Knop, E. et al, August 2017. Artificial light at night as a new threat to pollination. Nature.

Robertson, S.M., et al. 2021. Nocturnal Pollinators Significantly Contribute to Apple Production, Journal of Economic Entomology.