The pests that got away: Part 1

Red imported fire ant

By Denis Crawford

In the Pest Files of May 2024, I detailed several invasive pests which have established in parts of Australia. My thesis was that those invasive pests have something in common, the ability to travel long distances in horticultural material. In this article we look at the fire ant which has recently travelled well outside the biosecurity zones of southeast Queensland.

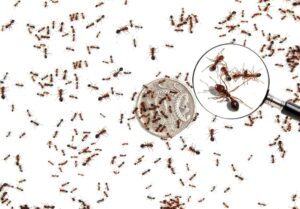

The fire ant (Solenopsis invicta) is an aggressive invasive pest which is more formally known as the ‘red imported fire ant’. The ant is native to South America and was first detected in Australia in Brisbane in 2001, although it may have arrived years earlier. The pest most likely arrived in shipping containers from North America.

Fire ants are omnivorous insects that have the potential to destroy crops, injure livestock, and devastate natural ecosystems by competing with and/or feeding on other insects and invertebrates. Fire ants defend their nests aggressively by swarming towards an intruder and stinging them. They are a significant public health problem. Reactions to their sting range from localised swelling to anaphylactic shock.

In the United States, fire ants first took hold in the 1930s and now infest more than 150 million hectares across 15 southern US states. The US Department of Agriculture estimates that fire ants cost the United States about $8.75 billion (US) annually. The impact on public health is equally massive. It is estimated that more than 14 million people are stung each year. The Australia Institute says there is no reason why fire ants would not have similar impacts in Australia if it spread out of southeast Queensland1.

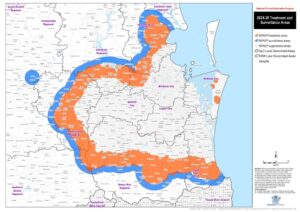

Fire ants currently infest about 850,000 hectares in southeast Queensland, as far north as the Sunshine Coast, west to the Lockyer valley and south to within a few kilometres of the New South Wales border. In July of 2025 eight fire ant nests were detected at the BHP Broadmeadow coalmine at Moranbah, a coal mining town about 150 kilometres inland from Mackay. That is over 700 kilometres from the closest known infestation in southeast Queensland.

How is that possible? Winged ants can fly about five kilometres, but that only happens at certain times of the year when nests release mating swarms of winged males and females. Fire ants can be spread much further with the movement of materials such as soil, hay, mulch, manure, quarry products, turf and potted plants. For this reason, infested areas of southeast Queensland have been declared biosecurity zones, with regulations governing movement of such material out of the zones to prevent long distance travel.

The Moranbah nests have been eradicated by crews from the National Fire Ant Eradication Program2, and exactly how the ants managed to travel over 700 kilometres is under investigation. Further surveillance and eradication work at the mine will continue for the next couple of years before the site can be declared fire ant-free. A program will be implemented to help locals in the area identify fire ant nests.

Insect growth regulators (IGR) such as pyriproxyfen and s-methoprene are the frontline weapons against fire ants. The IGRs are broadcast in a granulated bait form, so worker ants carry it back to the nest. The IGRs mimic natural insect hormones and disrupt the fire ant’s reproductive cycle by preventing the queen from laying viable eggs and impeding larval development. No eggs and little larval development mean worker ants are not replaced as they die, leading to the collapse of the ant colony.

Fire ant workers live for about six weeks so it may take three to six months for a nest to be eradicated using IGRs. Granular ant baits containing the insecticides indoxacarb and hydramethylnon are also registered against fire ants for broadcast in larger areas. Another bait containing the insecticide fipronil is also registered and is applied directly to the nest. The insecticides are quicker acting and control fire ant nests in three to five weeks.

An eradication area has been declared around the edge of the biosecurity zones in southeast Queensland. The aim is to work from the outside of the infestation and move inwards. This requires crews from the National Fire Ant Eradication Program to enter private properties to spread the ant baits. What could possibly go wrong? If COVID-19 taught us anything it was that some people do not like being told what to do. Crews from the eradication program sometimes require police escorts to gain access to private properties.

There is a lot of misinformation circulating on social media (go figure!) about the ant baits. One of the theories is that the ant baits will kill all the bees. Nope. The ant baits are attractive to fire ants because the bait is small pieces of corn grit soaked in soybean oil. Bees are attracted to flowers containing nectar and pollen and are uninterested in the baits. There was also concern about the impacts of the ant baits on pets. The compounds found in the ant baits are the same as in flea collars and other flea treatments applied directly to cats and dogs.

The consensus on the effect of fire ant baits on native ant species is that broadcast treatments with the baits have no long-term negative impacts on native ant populations3. Although impacted in the short term, the native ants move back into areas once the fire ants are gone. Importantly, the fire ants themselves have a far greater impact on native ants than any fire ant control treatment. Fire ants remain active during the mild winters of Queensland, and, for the first time, eradication treatments will continue through winter 2025 in parts of southeast Queensland. This further reduces the impact on native ants because the native ants are usually not as active during cooler months as the fire ants.

There have been occasional detections of fire ant across the border in northern New South Wales (NSW). Nests were found in South Murwillumbah (November 2023), Wardell (January 2024) and Tweed Heads (July 2025) and were subsequently destroyed. The NSW Department of Primary Industries (DPI) hope to control ‘the risk of fire ants entering NSW through human assisted movement’ and ‘if fire ants are found in NSW, they are contained and successfully eradicated’ 4.

Most of mainland Australia is climatically suitable for fire ants to establish. Fire ants are well known for rafting down rivers on debris or even forming ‘ant rafts’ of their own by joining together. It is possible that fire ants could enter NSW, Victoria and South Australia via the Murray Darling system. That would make the detection of fire ant nests in the coalmine at Moranbah seem quaint in comparison.

Federal and State governments have committed $593 million over four years (2024-27) for the National Fire Ant Eradication Program. That seems a bit short when this program’s own strategic review estimated that at least $200 to $300 million per year would be required. We need to put pressure on the Federal and all State governments to invest more. To paraphrase the title of the discussion paper by the Australia Institute, investment now will avoid a national disaster1.

References

- Le, M.N. & Campbell, R. (2024, April). Red imported fire ants – the benefits of avoiding a national disaster. The Australia Institute.

- National Fire Ant Eradication Program. (n.d.). New fire ant detection in Moranbah, Isaac region. Retrieved August 11, 2025, from https://www.fireants.org.au/about-us/news-and-events/media/detection-moranbah

- Invasive Species Council. (n.d.). Help stop fire ants in their tracks. Retrieved August 11, 2025, from https://invasives.org.au/our-work/invasive-insects/ants/red-fire-ants/

- NSW Fire Ant Team. (n.d.). NSW DPIRD Fire Ant Strategic Plan 2024-25. Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, New South Wales.

Denis Crawford

M: 0417 117 741

E: denisjcrawford@gmail.com