Seed dormancy issues of native Ericaceae

by James Wood

The propagation of plants can be performed vegetatively or with seed. In many circumstances vegetative propagation is essential to achieve immediate conservation outcomes, but if you want to achieve genetically diverse outcomes germinating seed is generally preferable. When it comes to the functioning of seed banks, germination is also important. Germination testing is the most meaningful measure of viability in seed collections, and seed banks need the ability to turn seeds back into plants. However, as anyone who has worked with seed will know germinating native seed is often very difficult, because seeds often have dormancy.

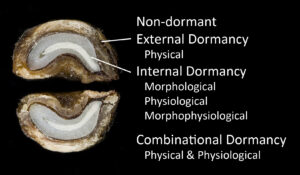

You can classify dormancies into four broad groups. Seeds that just go, seeds with an external physical barrier to water, those with an internal mechanism that needs to be unlocked, and finally a mixture of internal and external blocks.

So how difficult are these to deal with? Weirdly, non-dormant seeds are generally easy but you can encounter a picky species that just won’t move outside a narrow range of conditions. Physical dormancy is easy to deal with and the one most are familiar with – you just crack the coat to let the water in and you’re away. Things start getting tricky with the internal dormancies. Morphological dormancy can result in huge delays as the embryo develops in the seed, but at the other extreme, seed can germinate within a few weeks and you’d never know they were “dormant”. Physiological dormancy is probably the obstacle you’re most likely to encounter, with seeds responding to one or several environmental signals. Some species in this group are easy, requiring just a short stratification treatment, but others are more difficult or time consuming. Morpho-physiological is a mash-up of the previous two behaviours with embryo maturation reliant on an environmental trigger, but it can also cover stops in a seedling’s development too, which can be tricky. Finally, you have combinational dormancy where you crack the coat, chill the seeds and germination follows.

The Tasmanian Seed Conservation Centre (TSCC) has been conducting germination tests since 2006. The bulk of tests are conducted on petri dishes with a 1% agar gel, sometimes with a pinch of nitrate or a bit of smoke solution. We began with just two incubators, but we now have twelve. The TSCC has a team of eight volunteers who actually carry out the work, and it’s not a light commitment. Scoring is done weekly, and some tests can run for a long time.

Anything that germinates in under eight weeks I consider to be quick, but 9-20 weeks is normal. However, some of our tests can run for quite a while. If the seeds look healthy, we often just move tests into another incubator and move again every 2-5 months.

So how has TSCC been faring with the testing? About 45% of the collections we test germinate fairly easily. Another 15% of collections need a little pre-treatment to coax them into action. The remaining 45% however, are challenging. The difficulty level often follows families. Legumes are pretty straightforward, as are daisies, and grasses. But groups like the sedges and the heaths tend to be more difficult.

Tasmania has a lot of Ericaceae and they often form a significant part of the understorey. If we want to be able to restore or translocate many of our vegetation communities, efficient propagation of this group is very important. Many species are ornamental and their absence from horticulture is likely due, in part, to the heavy mycorrhizal requirements but also the challenges of propagation.

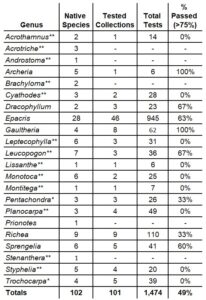

The table included with this article gives a breakdown of Ericaceae diversity in Tasmania, as well as the number of tested collections, total number of tests conducted, and the percentage of the tested collections that have achieved greater than 75% germination. We find that the loose-seeded species are easier to germinate, whereas the stone-fruited species are more challenging.

The bulk of stone-fruited species are germinating poorly and typically only do so after long periods of incubation. We’ve been making a concerted effort with a number of these species and we’re over ten years into working with Cyathodes, Leptecophylla and Planocarpa. In that time, we have had one collection of Planocarpa achieve 75% germination, but typically we’re getting between 0-20%. Regardless, the TSCC continues testing to resolve these issues. If you are interested in seeing what treatments we find work or fail, you can view our germination testing on the RTBG website at https://gardens.rtbg.tas.gov.au/conservation/tsccgerminationdatabase/

by James Wood

Manager Tasmanian Seed Conservation Centre

Royal Tasmanian Botanical Gardens

Department of Natural Resources and Environment Tasmania

T: (03) 6166 0977

Main photo: A selection of Tasmania’s native Ericaceae